On Edge

ABC, 123: planning out the On Edge art installation to scale.

Recently I was interviewed by a 13 yr old who asked me what the hardest part of my job is. “Time!” I said immediately. “Good lord, time management. Knowing what to prioritize when.” A week prior a journalist asked me about my relationship to time as if I knew some secret about detaching from the fast-paced pressures of the digital world given that I am a letterpress printer. Besides going to the mountains? Hell no, I said. I design with metal type because I’m faster with it than I am with pixels.

I feel slow about everything (i.e. when was my last blog post? when does one plant lettuce?). Only when I take annual stock of “big things I’ve done” do I feel even marginally on top of it. I know this is due to my voracious curiosity + lowkey anxiety + unflagging optimism + perfectionist – okay let’s call it what it is – obsessive compulsive tendencies. I mean, the details, you know. There are a lot of them.

I’m installing two art shows in the next two weeks. And again, evaluating my relationship to time. There is a long arc of think and feel that goes into making any kind of art. It seems like the simplest thing in the world so it is of course the hardest thing. To actually feel what you feel, not just think about it. Then to imagine, which means you have to pretend you feel utterly free and fearless long enough to pull a vision out of yourself. Then to synthesize, frame, and explain it. To ask over and over and over, what’s the point. What is the point. Why am I making this.

Something Einstein said rings true for me here: “You don’t really understand something unless you can explain it to your grandmother.” I have lunch with my grandmother every week and let me tell you, she asks difficult direct questions and she does not take any esoteric side-slipping for an answer. No obfuscation, no abstraction, no I-don’t-know or it’s-all-relative, nope. You gotta say it exactly like it is.

Parts to whole

My upcoming show On Edge at Core Gallery is an installation of Broken Broadside prints with related paintings. It’s an installation because it’s a lot of parts coming together to make a whole. About 300 prints and 10 paintings. I aim for the parts to hold their own out of context, but I’m going for an overall effect of “holy crap words make me feel something. I feel ________.” Fill in the blank. I don’t care much what you feel when you see it but I really want you to feel, to be connected to your insides, and to walk away with some words that help express that feeling. Also to carry with you a tangible reminder (read: small print) of that feeling for yourself or for others. Was that esoteric? Sorry grandma. I’m working on it!

Mocking up the Broken Broadside install with test prints and a blank canvas.

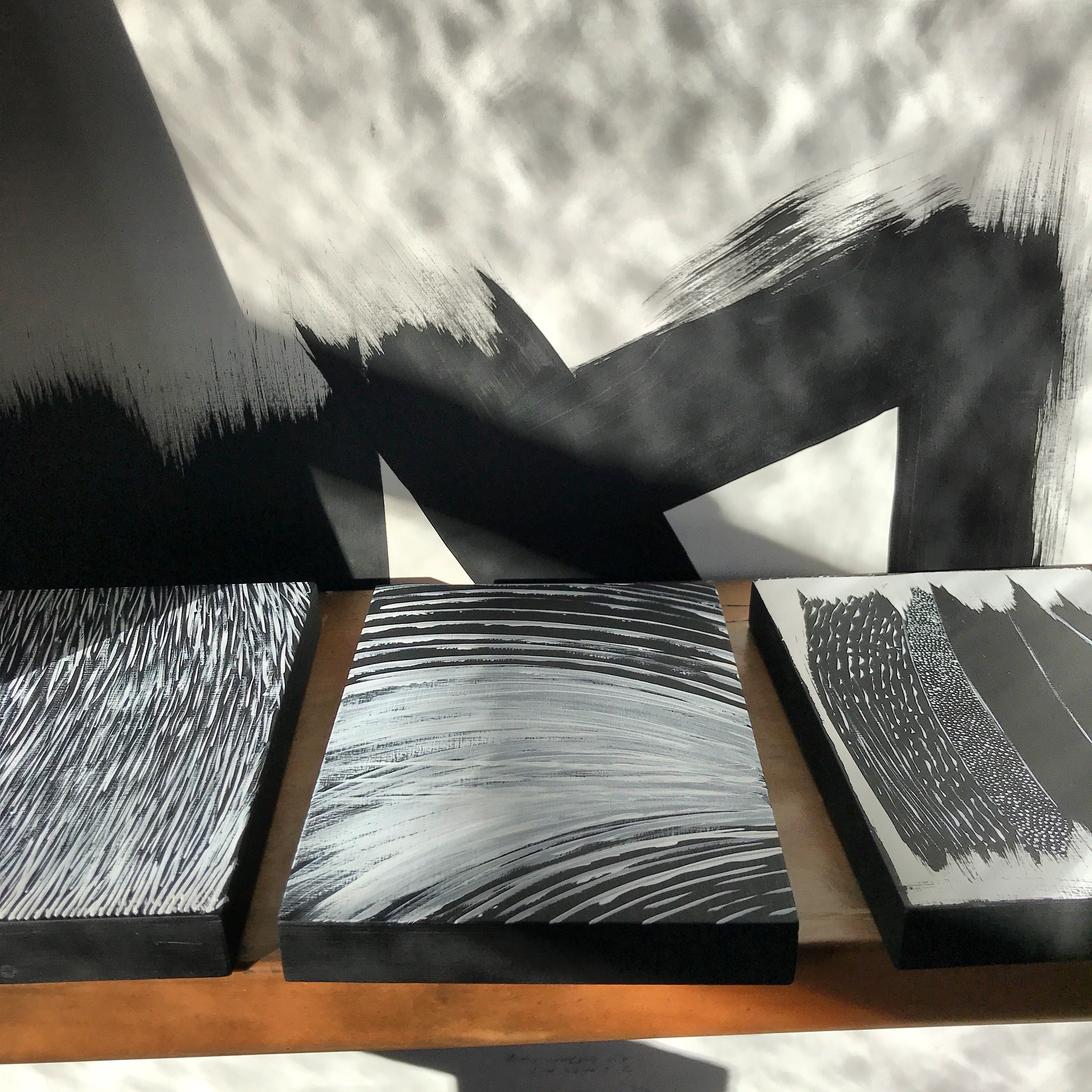

Black and white. Type. Letterpress prints in multiples paired with paintings of partial letters and the negative space between them, zoomed-in studies of parts of the prints.

The Broken Broadside series began three years ago with a conversation after a reading at Hugo House, where I met poet Cedar Sigo. We talked about edges and ephemera and he gave me the fistful of coffee-stained poems he’d just read on stage and said, “you know, if you ever want to do something with any of this.” When he said the word “this” he gave a loose, free wave of his hand over the letters on the page, and scribbled a half circle around a few lines at random. I am grateful to Cedar for a lot of things but I am most grateful for that moment of abandon, of total freedom that he communicated to me as he handed me his long-belabored still-in-progress work of the day (which has since coalesced into his stellar new book The Royals, just out from Wave).

Wait, what’s a Broken Broadside?

Since that initial conversation with Cedar, I’ve worked with ten more poets (6 of whom are reading at the gallery on April 25!) on the project and it almost doesn’t need explaining anymore. But for the record: Broken Broadsides are one-color prints of poetry fragments, selected from new works that are submitted by their authors with full intent to have them excerpted and treated to experimental typography.

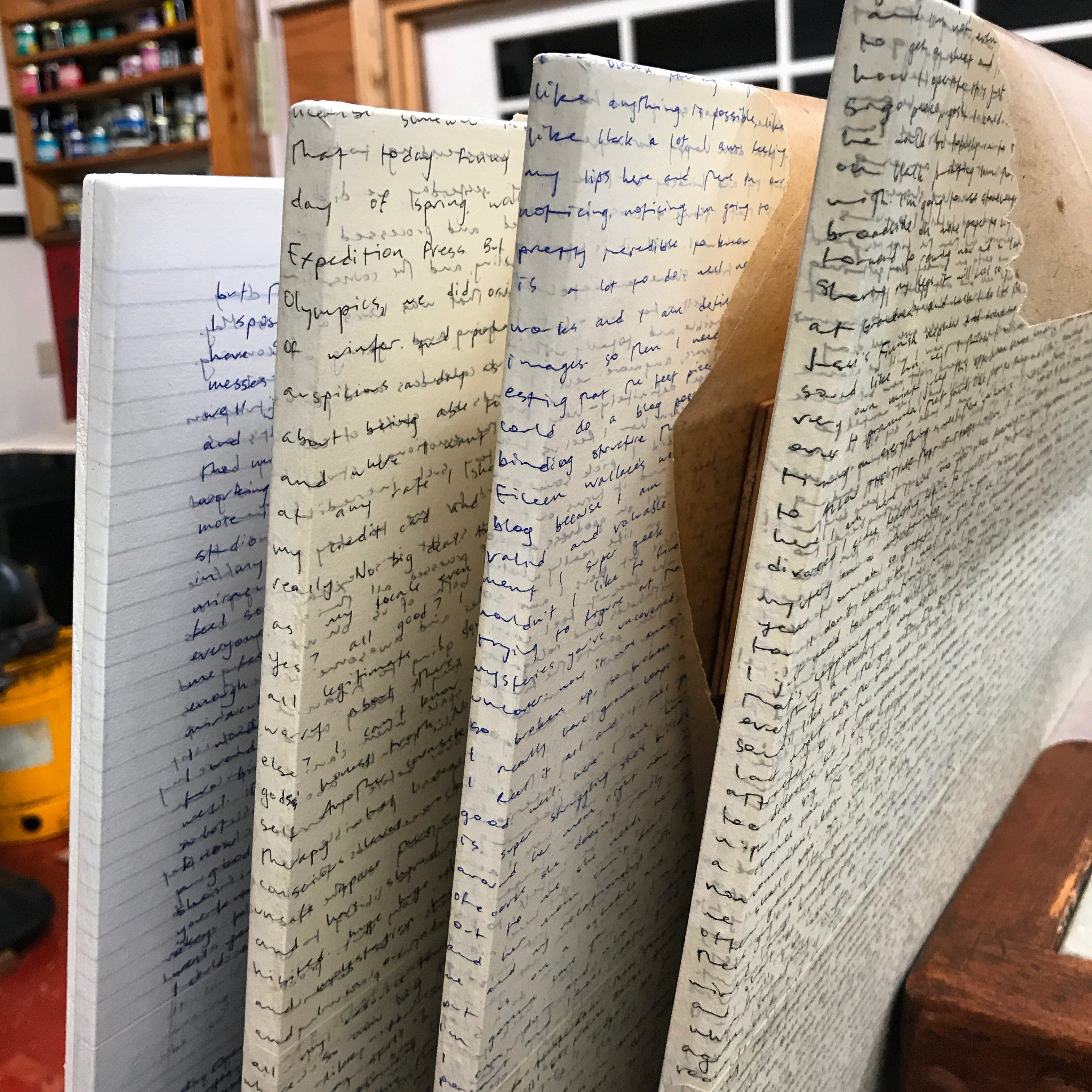

Broken Broadsides 2 – 7: Pai, Ellis, Spaulding, Gilroy, Wong, Dunic.

What I’m going for with these prints is emotion that strikes. My selection criteria is based on how hard the lines hit my gut and how uncomfortable it is to hold them. Then, how long they stick around. That’s how I pick.

Here’s the process: either I reach out or a poet contacts me with a submission, typically a few new unpublished poems. I sit with the words for months, and when I settle on a selection I email the poet for approval. Then I draw thumbnail sketch after thumbnail sketch and pull letters out. When I get a proof that makes me feel awe I snap a photo and excitedly send it to the poet. About 30 seconds after I hit send I feel terribly vulnerable and afraid of what they will think, and I have to marshal my nervous insides until I get a response, which is usually along the lines of: “Wow. I never saw it that way. I love it!” This risk, this feeling of things at stake, is what makes it such a strong exchange I suppose. It’s also how trust gets built.

On separating and coming together

I’m tired of trying to separate my artist self from my printer/publisher self. What with my solo show at Core this year being scheduled during National Poetry Month, I decided, so what. Both and. And both. Is it confusing all this different work I’m doing across disciplines and media? Well I admit sometimes I am dizzy with it and mighty distracted to the point where I put on two different shoes and don’t realize it till halfway through the day. I spend a lot of time distinguishing and clarifying, and I do make a lot of different lists. But less and less do the categories matter. I am here where all the disparate things I do come together, and I’m determined to quit trying to be elsewhere.

The last time I wrote on this identity split was in my initial post about Broken Broadsides, so it makes sense that this show is bringing them together consciously, the artist and the publisher. I feel really excited when I think about it that way. I feel like, hell yeah! I can make shit public! That’s how I think about publishing: making things public. Whether in a book or on a billboard. It’s hard to explain how immensely gratifying it is to be entrusted with well-crafted words from authors I admire, and apply my own craft to make them more visible in the world. I am so deeply honored every time. I’ve built a strange skillset between my editorial and aesthetic sensibilities and I’m using it. I’m using it as far as I can see and past. When I get to the edge I start imagining again.

Outside/in, inside/out

The prints in this show are the most public part. They are easy to see and tell what they are, the words are there, called out, and the poet’s names are there too. They have already been broadcast all over social media and shipped around the world and continue to be passed hand to hand. The paintings are more private. They mostly don’t even exist yet outside of my mind and heart. They are pre-existing in my studio right now, many smooth blank white wooden panels awaiting black marks.

New studio set-up at home. What else is a living room for?

It’s strange this process but it works. I mean it’s working. I mean, this is me working. Stitching the outside in, the inside out. Allowing them to breathe and blend together. Long dark night of the soul, anyone? I’ve got you covered. I’m making the traverse. I’m reaching in and I’m reaching out and it hurts. It’s hard to keep being so real and forget you, the viewer, yes you, dear reader. I’m thinking of you all the time but I have to forget you to make the work. Only when I make the work completely for myself can anyone else hope to find any use in it. I hope you do. I hope you find something in the words, or the space between them, that makes your heart sing. No matter how blue the tune.

--------------------------------------------------

“The quality of light by which we scrutinize our lives has direct bearing upon the product which we live, and upon the changes which we hope to bring about through those lives. It is within this light that we form those ideas by which we pursue our magic and make it realized. This is poetry as illumination, for it is through poetry that we give name to those ideas which are, until the poem, nameless and formless-about to be birthed, but already felt. That distillation of experience from which true poetry springs births thought as dream births concept, as feeling births idea, as knowledge births (precedes) understanding.

As we learn to bear the intimacy of scrutiny, and to flourish within it, as we learn to use the products of that scrutiny for power within our living, those fears which rule our lives and form our silences begin to lose their control over us.” – Audre Lorde, opening lines from “Poetry is not a Luxury,” Sister Outsider

“I have not been able to touch the destruction within me.” – Audre Lorde, from “Power,” The Black Unicorn